Chapter 21 SUMMARY

Poverty, Inequality, and Discrimination

Chapter 21 begins with a survey of the basic facts of poverty and income distribution in the United States. It then turns to explanations of differences in incomes and policy measures to change the distribution of income. Throughout, the chapter emphasizes the trade-off between equality and efficiency.

Chapter Outline

Issue: Were the bush tax cuts “unfair”?

The recent tax cuts are highly controversial.

The question relates to whether or not it is equitable to give upper-bracket taxpayers a disproportionate share of the tax cuts.

The Facts: Poverty

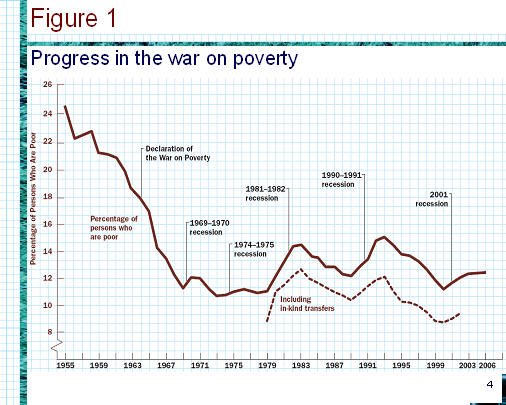

President Johnson declared a “War on Poverty” in 1964.

Counting the Poor: The Poverty Line

The dividing line between the poor and non-poor is the poverty line.

Poverty in the United States fell from the 1950s to the 1970s; since the late 1970s poverty has gone up and down with no clear trend.

Absolute versus Relative Poverty

There are both absolute and relative concepts of poverty.

An absolute concept of poverty says that if you fall short of a certain minimum standard of living, you are poor; once you pass this standard, you are no longer poor.

A relative concept of poverty says that the poor are those who fall too far behind the average income.

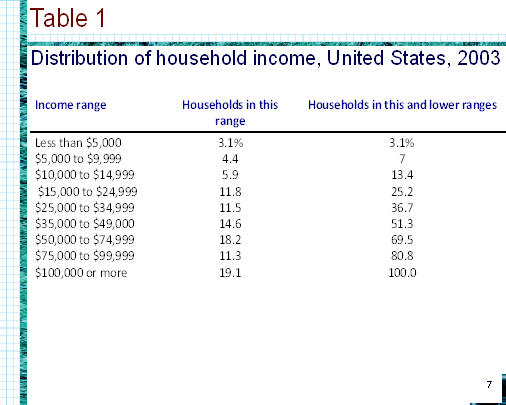

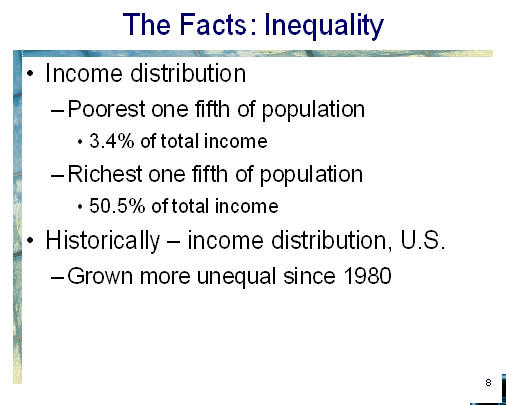

The Facts: Inequality

A market system such as the United States generates considerable inequality in the distribution of personal incomes.

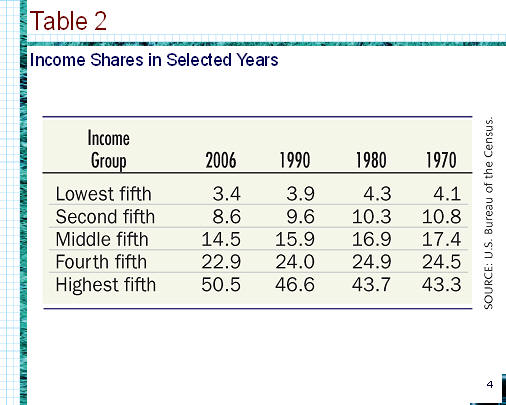

The poorest 20 percent of Americans earn only about 3.5 percent of personal incomes.

Since 1980, the distribution of income in the U.S. has grown substantially more unequal.

Some Reasons for Unequal Incomes

Among the reasons for differences in incomes are:

1. Differences in ability

2. Differences in intensity of work

3. Risk taking

4. Compensating wage differentials

5. Schooling and other types of training

6. Work experience

7. Inherited wealth

8. Luck

The Facts: Discrimination

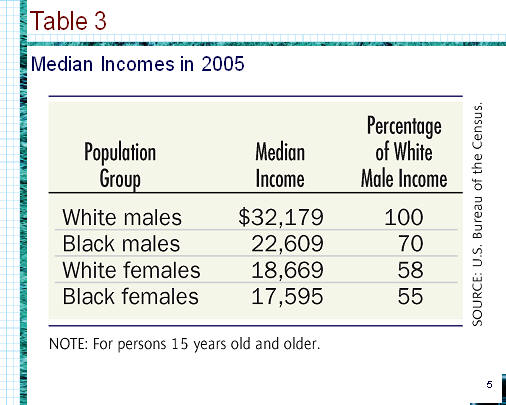

Women and non-whites typically have lower earnings than white males.

Part, but only part, of the explanation for this is discrimination.

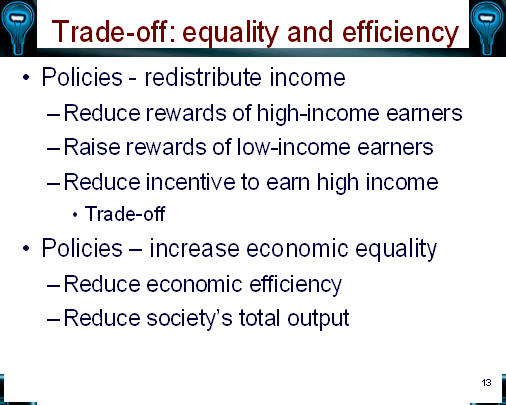

The Trade-Off between Equality and Efficiency

People have different marginal utility schedules, so some inequality can probably be justified.

However there is a formidable obstacle: The total amount of income in society is not independent of how we try to distribute it.

The optimal income distribution always involves some inequality.

We should remember two important points:

1. There are better and worse ways to promote equality. In pursuing further income equality (or fighting poverty), we should always seek policies that do the least possible harm to incentives.

2. Equality is bought at a price. Thus, like any commodity, society must rationally decide how much to “purchase.” We will probably want to spend some of our potential income on equality, but certainly not all of it.

Policies to Combat Poverty

Education as a Way Out

Education is not an effective way to lift adults out of poverty. Its effects are delayed for a generation or more.

The Welfare Debate and the Trade-Off

Anti-poverty programs include education, public assistance programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, food stamps, and government provision of goods and services such as medical care and subsidized public housing.

All are controversial, and public assistance programs have been under particularly strong attack.

The debate over welfare centers on two questions: how much equality should the society buy, and how much inefficiency in the pursuit of equality is tolerable?

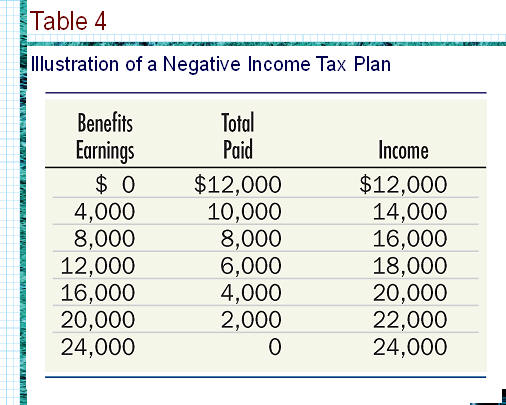

The Negative Income Tax

A negative income tax guarantees a minimum income, then cuts back the subsidy as earned income rises, until eventually a break-even income is attained at which there is no further subsidy.

The operative formula is: guarantee = tax rate ´ break-even level.

The Negative Income Tax and Work Incentives

The work incentive depends on the marginal tax rate.

Under some current welfare programs that rate is 100 percent, so the negative income tax, with a rate of less than 100 percent, probably would improve work incentives.

OTHER POLICIES TO COMBAT INEQUALITY

The Personal Income Tax

A progressive income tax can reduce inequalities in the society.

The current American income tax changes the distribution of income only modestly, however.

Death Duties and Other Taxes

Taxes on inheritances and estates can reduce inequality, but they are too small in the United States to have much effect.

Most other taxes are regressive.

Overall, then, the United States tax system is only slightly progressive.

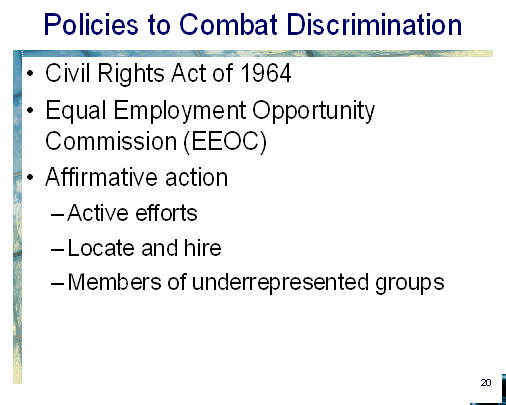

POLICIES TO COMBAT DISCRIMINATION

Firms and other organizations with suspiciously small representations of minorities or women in their workforces were required not just to end discriminatory practices but also to demonstrate that they were taking affirmative action to remedy this imbalance.

Critics claim that affirmative action amounts to numerical quotas and compulsory hiring of unqualified workers simply because they are black or female.

If this allegation is true, it exacts a toll on economic efficiency.

Proponents of affirmative action argue that affirmative action is needed to redress past wrongs and to prevent discriminatory employers from claiming that they are unable to find qualified minority or female employees.

The difficulty revolves around the impossibility of deciding who is “qualified” and who is not based on purely objective criteria.

A LOOK BACK

The market mechanism is extraordinarily good at promoting efficiency, but not very good at promoting equality.

APPENDIX

Margin Definitions

Poverty Line: an amount of income below which a family is considered “poor.”

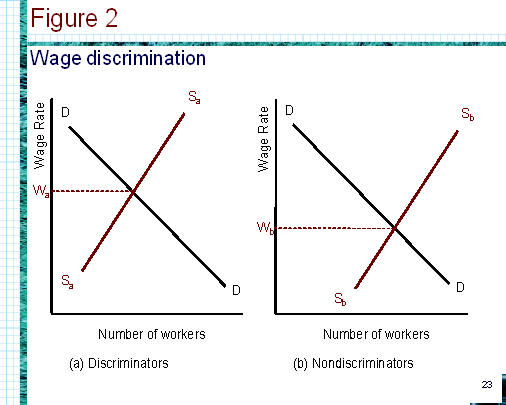

Economic Discrimination: occurs when equivalent factors of production receive different payments for equal contributions to output.

Affirmative Action: active efforts to locate and hire members of underrepresented groups.

Statistical Discrimination: occurs when the productivity of a particular worker is estimated to be low just because that worker belongs to a particular group (such as women).

Major Ideas

1. Both poverty and inequality declined in the United States after the Second World War then rose in the 1980s and 1990s.

2. Individual incomes differ for many reasons. Differences in native ability, in the desire to work hard and to take risks, in schooling and experience, and in inherited wealth all account for income disparities. Discrimination also plays a role. All of these factors, however, explain only part of the inequality that we observe. A portion of the rest is due simply to good or bad luck, and the balance is unexplained.

3. Prejudice against a minority group may lead to discrimination in rates of pay, or to segregation in the workplace, or to both. However, discrimination may also arise even when there is no prejudice (this is called statistical discrimination).

4. There is a trade-off between the goals of reducing inequality and enhancing economic efficiency: Policies that help on the equality front normally harm efficiency, and vice versa.

5. Whatever goal for equality is selected, society can gain by using more efficient redistributive policies because such policies let us buy any given amount of equality at a lower price in terms of lost output. Economists claim, for example, that a negative income tax is preferable to our current welfare system on these grounds.

6. The goal of income equality is also pursued through the tax system, especially through the progressive federal income tax and death duties. But other taxes are typically regressive, so the tax system as a whole is only slightly progressive.